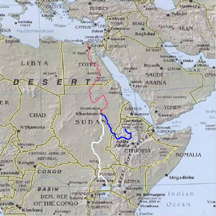

The Nile River from space

| This is a work in progress: lots of writing, formatting, revising, proofing left to do! — David McMurrey |

The choppy sentences chapter suggests that otherwise literate writers use the short simple writing style because they think it will be so much clearer for their readers. That's quite like those writers who use all caps, bold, larger font sizes to make readers read their message. In both cases, the effect is just the opposite. Readers avoid text that seems to scream at them, and they give up on text that jerks along, starting and stopping every five or six words.

Whereas short-sentence writers seem obsessed with an illusory simplicity and clarity, long-sentence writers are obsessed with the interconnectedness and interrelatedness of everything. Ending one sentence and beginning a new one seems to threaten the whole communicative enterprise!

However, that's what we have transitions for. They ensure that continuity, context, and relatedness are maintained, that readers can follow along without suffocating from overly long sentences.

In this chapter, you'll practice fixing overly long sentences in such a way that you improve clarity and readability but still maintain continuity.

As mentioned in the choppy-writing chapter, nothing is wrong with sentences that jump outside of the standard 14 to 22 word-length range. Any decently written text will have plenty of sentences that are shorter than 14 words and plenty that are longer than 22 words. Variety is a good thing. Even so, some lengthy sentences just overdo it:

Overly long version: Literally, sustainable development refers to maintaining development over time, although by the early 1990s, more than 70 definitions of sustainable development were in circulation, definitions that are important, despite their number, because they are the basis on which the means for achieving sustainable development in the future can be built.

Is this 50-word monster tough reading? Maybe not the most difficult you've ever encountered, but still unnecesarily uncomfortable to read. Simplify it by diagramming the main ideas:

Diagrammed version:

1 Literally, sustainable development refers to maintaining development over time,

2 by the early 1990s, more than 70 definitions of sustainable development were in circulation

3 definitions that are important, despite their number,

4 they are the basis on which the means for achieving sustainable development in the future can be built

You could break it out even further, but this ought to be enough. The next step is to paraphrase these parts of the original sentence:

Paraphrased version:

1 Literally, sustainable development refers to maintaining development over time.

2 By the early 1990s, more than 70 definitions of sustainable development were in circulation

3 These definitions that are important, despite their number, because they are the basis on which the means for achieving sustainable development in the future can be built

As you can see, sentences 3 and 4 of the diagrammed version can easily be recombined in this paraphrased version. The resulting length is not a problem. Here's one possible simplification:

Revision: Literally, sustainable development refers to maintaining development over time. However, by the early 1990s, more than 70 definitions of sustainable development were in circulation. Despite their number, these definitions are important because they are the basis on which the means for achieving sustainable development in the future can be built.

When you simplify an overly long sentence, it's fairly easy to locate the break points. Here, we make one sentence three sentences. Doing so also gives you extra room to make things clearer. For example, the writer might want to further emphasize that having so many definitions is a good thing because it enables a more all-encompassing sense of the term.

The preceding revision used the syntax of the original sentence to find break points where new sentences could be started. Another way to think about the process is to take an inventory of the main ideas that a sentence contains. The original sentence above had at least three main ideas. Count the main ideas in this one:

Overly long version: During the 1960s, development thinking, encompassing both ideology and strategy, prioritized economic growth and the application of modern scientific and technical knowledge as the route to prosperity in the underdeveloped world and defined the "global development problem" as one in which less developed nations needed to "catch up" with the West and enter the modern age of capitalism and liberal democracy, in short, to engage in a form of modernization that was equated with westernization (and an associated faith in the rationality of science and technology).

Sentence length: The standard range is considered 14 to 22 words. However, this is an average: plenty of sentences in well-written document go below and above this range.A new record—86 words! The main ideas include the following:

Let's see if we can get these four main ideas into their own separate sentences:

Revision:

1 During the 1960s, development thinking, encompassing both ideology and strategy, prioritized economic growth through the application of modern scientific and technical knowledge.

2 This notion was considered the route to prosperity in the underdeveloped world.

3 The "global development problem" was defined as one in which less developed nations needed to "catch up" with the West and enter the modern age of capitalism and liberal democracy.

4 In short, they needed to engage in a form of modernization that was equated with westernization (and an associated faith in the rationality of science and technology).

This revision cheats a bit but legitimately so. Ideas 1 and 2 end up in a sentence together. Sentence 2 is a new creature we did not define as a main idea. However, it is certainly implied in the original, and it brings out this important idea much better. When you unpack overly long sentences, you will discover that you have more verbal "elbow room" to express ideas more clearly. Notice that this clarification also occurs in the phrase economic growth through the application of modern scientific and technical knowledge. Notice that in the original these ideas were linked by the word and. The word through sets up a sharper clearer relationship between these two things: growth is achieved through science and technology.

You can practice this method in the sentence-diagramming chapter.

It would be difficult—and probably impractical—to state a formula or strategy for breaking down overly long sentences. It should be fairly intuitive where to break up long sentences and start new, shorter sentences. It should also help to take an inventory of the main ideas. Get some practice now revising overly long sentences. Cover up the revisions as you go, think through your own revision, and then compare. If you are stumped, read the hints in between the originals and revisions.

Overly long version: In the classical theory of gravity, which is based on real space-time, the universe can either have existed for an infinite time or else it had a beginning at a singularity at some finite time in the past, the latter possibility of which, in fact, the singularity theorems indicate, although the quantum theory of gravity, on the other hand, suggests a third possibility in which it is possible for space-time to be finite in extent and yet to have no singularities that formed a boundary or edge because one is using Euclidean space-times, in which the time direction is on the same footing as directions in space.

Don't worry about the science here. A good technical writer or editor, totally lacking physics background, could whip this 108-word monster into shape and never harm the scientific content. I see two main ideas about the universe based on two possibilities using the classical theory of gravity. A third main idea links singularity theorems with the second possibility. A fourth idea links the quantum theory of gravity with a third possibility. A fifth idea establishes a rationale for the fourth idea. Maybe you can work up five sentence, each one featuring one of these main ideas.

Revision: In the classical theory of gravity, which is based on real space-time, there are only two possible ways the universe can behave. Either it has existed for an infinite time, or else it had a beginning at a singularity at some finite time in the past. In fact, the singularity theorems show it must be the second possibility. In the quantum theory of gravity, on the other hand, a third possibility arises. Because one is using Euclidean space-times, in which the time direction is on the same footing as directions in space, it is possible for space-time to be finite in extent and yet to have no singularities that formed a boundary or edge. —Stephen W. Hawking, The Theory of Everything

Notice in this revision how the word possibility is used to keep us readers focused. You probably haven't a clue—any more than I who avoided physics at all costs—as to what singularity theorems, the quantum theory of gravity, or Euclidean space-times are, but you can see the basic structure of the sentence.

Overly long version: The quantum theory of gravity opens up a new possibility in which there would be no boundary to space–time and, thus, no need to specify the behavior at the boundary because there would be no singularities at which the laws of science broke down and because there would be no edge of space–time at which one would have to appeal to God or create some new law to set the boundary conditions for space-time.

What are the syntactical break points here: in which looks like a strong possibility; thus looks like another; the two instances of because are two more. Thus, maybe you can break this 76-word gem down into 4 sentences. What about main ideas? There's the main idea indicated by new possibility; two more indicated by no boundary and no need; still, two more indicated by the two instances of because. This analysis suggests 5 simpler sentences. Give it a shot.

Revision: The quantum theory of gravity has opened up a new possibility. With this theory, there would be no need for a boundary to space–time. Thus, there would be no need to specify the behavior at the boundary. In other words, the quantum theory of gravity eliminates the need for singularities at which point the laws of science break down and the need for an edge of space–time at which one would have to appeal to God or create some new law to set the boundary conditions for space-time. —Stephen W. Hawking, The Theory of Everything

Notice what gets added in the revision. The word need is repeated like crazy. Sentence 3 more or less restates sentence 2, but echoing the all-important need. It can'y be repeated enough: this kind of repetition is good—it helps readers follow the discussion.

Overly long version: The explanation that is usually given as to why we don’t see broken cups jumping back onto the table is that it is forbidden by the second law of thermodynamics, which states that disorder or entropy always increases with time, such that an intact cup on the table is a state of high order, but a broken cup on the floor is a disordered state, a fact that indicates that one can therefore go from the whole cup on the table in the past to the broken cup on the floor in the future, but not the other way around.

Need some hints? Looks like which states is a break point as well such that and a fact that.

Revision: The explanation that is usually given as to why we don’t see broken cups jumping back onto the table is that it is forbidden by the second law of thermodynamics. This [law] says that disorder or entropy always increases with time. An intact cup on the table is a state of high order, but a broken cup on the floor is a disordered state. One can therefore go from the whole cup on the table in the past to the broken cup on the floor in the future, but not the other way around. —Stephen W. Hawking, The Theory of Everything

Overly long version: Suppose a systems starts out in one of the small number of ordered states, then as time goes by, the system evolves according to the laws of physics and its state changes, then at a later time, there is a high probability that it will be in a more disordered state, simply because there are so many more disordered states——the implication of which is that disorder will tend to increase with time if the system obeys an initial condition of high order.

How many ideas? Maybe six or seven: the starting state, the next state, a following state, increasing disorder with time, increasing number of disordered states, the reason for that disorder. How many syntactical segments? Probably five, with break points at then, then at a later time, simply because, and the implication.

Revision: Suppose a systems starts out in one of the small number of ordered states. As time goes by, the system will evolve according to the laws of physics and its state will change. At a later time, there is a high probability that it will be in a more disordered state, simply because there are so many more disordered states. Thus, disorder will tend to increase with time if the system obeys an initial condition of high order. —Stephen W. Hawking, The Theory of Everything

Overly long version: A computer memory is basically some device that can be in either one of two states, an example of which is a superconducting loop of wire where, if there is an electric current flowing in the loop, it will continue to flow because there is no resistance while, on the other hand, if there is no current, the loop will continue without a current——two states of memory that can be labelled “one” and “zero.”

Your turn!

Revision: A computer memory is basically some device that can be in either one of two states. An example would be a superconducting loop of wire. If there is an electric current flowing in the loop, it will continue to flow because there is no resistance. On the other hand, if there is no current, the loop will continue without a current. One can label the two states of the memory "one" and "zero." —Stephen W. Hawking, The Theory of Everything

If you are confident you can simplify overly long sentences, try your hand at this exercise:

Now for some perverse fun. See if you can construct mercilessly long sentences—but which are still grammatically correct.

Original version: Before Darwin, American scientists typically accepted the biblically orthodox view that God directly created every type of species, with each thereafter reproducing true to form. In contrast, Darwin proposed that the interaction of several biological mechanisms naturally caused some descendants of older species gradually to evolve over countless generations into the ancestors of new species.

The simplest way of creating an overly long sentence is to merge two separate sentences into one: either as two independent clauses or as one dependent and one independent clause.

Overly long version: Before Darwin, American scientists typically accepted the biblically orthodox view that God directly created every type of species, with each thereafter reproducing true to form, whereas Darwin proposed that the interaction of several biological mechanisms naturally caused some descendants of older species gradually to evolve over countless generations into the ancestors of new species. [54 words!]

Original version: A popular crusade against instruction on the theory of evolution in public high schools erupted in America during the early 1920s. Led by the influential Democratic politician William Jennings Bryan, the crusade focused on enacting state statutes to bar teaching human evolution and, at least in part, represented a response to the spread of secondary education, which was then carrying evolutionary concepts to the general public to an unprecedented extent.

One of the main techniques for overly long sentences is to reduce independent clauses to dependent clauses and then to embed them in an independent clause.

Overly long version: Led by the influential Democratic politician William Jennings Bryan, who wanted to enact statutes to bar teaching human evolution in secondary education, which was then carrying evolutionary concepts to the general public to an unprecedented extent, a popular crusade against instruction on the theory of evolution in public high schools erupted in America during the early 1920s. [57 words]

Original version: After a series of near misses and the imposition of lesser restrictions in several places, in 1925, Tennesee became the first state to outlaw evolutionary teaching. William Jennings Bryan, an attorney as well as a politician, took his crusade to the courtroom when the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) instigated a judicial challenge to the Tennessee statute. In the ensuing trial of science teacher John Scopes, Bryan successfully sparred with Clarence Darrow, who represented the defendant, over science, religion, and academic freedom.

Another technique for creating cruelly long sentences is to use compound predicates. Notice that William Jennings Bryan does two things in this sentence: he took his crusade somewhere and he sparred with somebody. Rework these sentences around that idea.

Overly long version: After a series of near misses and the imposition of lesser restrictions in several places, in 1925, Tennesee became the first state to outlaw evolutionary teaching when William Jennings Bryan, an attorney as well as a politician, took his crusade to the courtroom to battle the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which had instigated a judicial challenge to the Tennessee statute barring the teaching human evolution, and successfully sparred with Clarence Darrow, who represented the defendant, John Scopes, over science, religion, and academic freedom. [84 words!]

Original version: Widespread demands for better science instruction led to the creation of the federally funded Biological Science Curriculum Study, which gave a prominent place to evolution in its popular tenth-grade textbooks. When these widely used evolutionary textbooks clashed with the surviving laws against evolutionary teaching in the mid-sixties, the United States Supreme Court in Epperson v. Arkansas used newly expanded constitutional restrictions against the establishment of religion to void the old statutes. This ruling made much of the modern acceptance of evolution.

You can create mercilessly long sentences by piling up dependent clauses (usually begin with that or which), one after another.

Overly long version: When these widely used evolutionary textbooks, made possible by widespread demands for better science instruction which led to the creation of the federally funded Biological Science Curriculum Study, which gave a prominent place to evolution in its popular tenth-grade textbooks, clashed with the surviving laws against evolutionary teaching in the mid-sixties, the United States Supreme Court in Epperson v. Arkansas used newly expanded constitutional restrictions against the establishment of religion to void the old statutes——a ruling that contributed to the modern acceptance of evolution. [85 words]

Original version: Because these demands of equal time for the biblical account of creation ran up against the same constitutional barriers invoked by Epperson against anti-evolution laws, creationists concentrated on securing equal time for biblical evidence that purportedly supported their beliefs. The Arkansas and Louisiana legislatures rewarded them in 1981 by mandating balanced treatment for "creation science" and "evolution science" in public schools. The passage of these statutes brought the ACLU back on the scene to successfully challenge both laws in court. The first statute was overturned in 1982, and the second in 1985. However, this court action has done little to reduce the creation-evolution legal controversy, as both sides continue to battle over the content of high-school biology instruction.

You can do this. Notice that creationists concentrated on something; then they were rewarded by something. You can combine the first two sentences based on this idea. The third sentence can be reduced to a big participial phrase (hint: convert brought to bringing). You can hook the fourth sentence to the end of the revised third. Now, we all know that However can be changed to although, thus turning the fifth and final sentence into a dependent clause. Simple!

Overly long version: Because these demands of equal time for the biblical account of creation ran up against the same constitutional barriers invoked by Epperson against anti-evolution laws, creationists concentrated on securing equal time for biblical evidence that purportedly supported their beliefs and were rewarded when the Arkansas and Louisiana legislatures in 1981 mandated balanced treatment for "creation science" and "evolution science" in public schools, bringing the ACLU back on the scene to successfully challenge both laws in court which overturned them in 1982 and 1985, although this court action has done little to reduce the creation-evolution legal controversy, as both sides continue to battle over the content of high-school biology instruction. [111 words!]

Original version: The creation-evolution legal actions primarily represented efforts to reconcile public science——that is, publicly supported science teaching and related activities——with popular opinion. This process was reflected in legal actions during the twenties banning the teaching of evolution in response to strong public opposition to Darwinism. It was later reflected in the Supreme Court's overturning of such bans after the public seemed to display a marked deference to scientific opinion. And, finally, it was reflected in increasing activity toward granting equal time for creationism when public opinion favored such fairness for competing "biblical" ideas.

A neat writing trick involves what Joseph M. Williams in calls the summative modifier. Here, let's call it a summative appositive, because grammatically, that's more specifically what it will it be. The second sentence already has it set up for you. Just rephrase a bit so that it becomes a phrase with a dependent clause embedded in it. Notice how the phrase This process summarizes (summatizes?) the main idea of the preceding sentence. In the final three sentences, notice that each is based on the verb reflected. These can be strung together in a series of three: another useful—but in this case, devious—trick for creating longer sentences.

Overly long version: The creation-evolution legal actions primarily represented efforts to reconcile public science——that is, publicly supported science teaching and related activities——with popular opinion, a process that was reflected in legal actions during the twenties banning the teaching of evolution in response to strong public opposition to Darwinism, in the Supreme Court's overturning of such bans after the public seemed to display a marked deference to scientific opinion, and finally in increasing activity toward granting equal time for creationism when public opinion favored such fairness for competing "biblical" ideas. [86 words—big deal]

Original version: Typically, legislators showed greater responsiveness to popular opinion than judges. However, even the courts operated within parameters established by popular sentiment. Public science could never deviate too far from popular opinion. In crafting this reconciliation, both legislators and judges avoided ruling on the scientific merits of evolution or creation. They typically viewed such merits as being beyond the scope of their competence. Instead, they based their decisions on non-scientific factors, such as the religious nature of creationism or the social ramifications of evolutionary teaching. Scientific opinion inevitably influenced these decision-makers, but often only to the extent it was distilled through popular opinion, either directly in the acceptance of a theory of origins or indirectly in the cultural respect afforded science generally.

Here's one that challenges and may consume all your linguistic heroism. The first two sentences can be combined with a simple, well-known three-word coordinating conjunction. The third sentence can be brought in by converting it to a big participial phrase (hint: use allowing). Add the fourth sentence by converting it to one of those summative appositives built on reconciliation. Sentences 5 and 6 can be reduced to a single dependent clause containing a compound predicate and added to what's left of sentence 4. (Those legislators and judges both viewed something and based on something.) Reduce the final sentence to a big participial phrase containing a dependent clause. After all, it modifies those same legislators and judges.

Overly long version: Typically, legislators showed greater responsiveness to popular opinion than judges, but even the courts operated within parameters established by popular sentiment, never allowing public science to deviate too far from popular opinion, a reconciliation in which both legislators and judges avoided ruling on the scientific merits of evolution or creation, which they typically viewed as being beyond the scope of their competence and based their decisions on non-scientific factors, such as the religious nature of creationism or the social ramifications of evolutionary teaching, inevitably influenced by scientific opinion only to the extent that opinion was distilled through popular opinion either directly in the acceptance of a theory of origins or indirectly in the cultural respect afforded science generally.

Had enough? Well, I have. If you can use the various sentence-lengthening tricks shown here to create fiendishly overly long sentences, try your hand at this exercise:

Links to these exercises are provided at the end of the sections where they are relevant. But here they all are in case you read the text straight through:

Return to the table of contents

Information and programs provided by admin@mcmassociates.io.