Please click here to help David McMurrey pay for web hosting: Donate any amount you can!

Online Technical Writing will remain free.

Technical reports and instructions often require cross-references—those pointers to other places in the same document or to other information sources where related information can be found.

A cross-reference can help readers in a number of different ways:

- It can point them toward more basic information if, for example, they have entered into a document over their heads.

- It can point them to more advanced information if, for example, they already know the stuff you're trying to tell them.

- Also, it can point them to related information.

Related information is the hardest area to explain because ultimately everything is related to everything else—there could be no end to the cross-references. But here's an example from DOS—that troll that lurks inside PC-type computers and supposedly helps you. There are several ways you can copy files: the COPY command, the DISKCOPY command, and XCOPY command. Each method offers different advantages. If you were writing about the COPY command, you'd want cross-references to these other two so that readers could do a bit of shopping around.

Of course, the preceding discussion assumes cross-references within the same document. If there is just too much background to cover in your document, you can cross-reference some external website, book, or article that does provide that background. That way, you are off the hook for having to explain it all!

Components of Cross-References

Cross-references can be internal (within the same document) or external (outside of the current document). Most cross-refencing guidelines depend on whether the cross-reference is internal or external. With external sources, you cannot control the titles of books, chapters, headings, page numbers. They are likely to change!

With cross-references to external documents:

- Do not cite titles of books, chapters, headings exactly word-for-word verbatim. Instead, refer to the general topic covered.

- Do not cite exact chapter or section numbers or exact page numbers.

Now, a decent cross-reference consists of several elements:

- Name of the source being referenced—This can either be the title or a general subject reference. If it is a chapter title or a heading, put it in quotation marks; if it is the name of a book, magazine, report, or reference work, put it in italics. (Individual article titles also go in quotation marks.)

- Page number—Required if it is in the same document. If the cross-reference is to the beginning of a chapter and the chapter number and title are cited (either internal or external), no need for the page number. Readers can use the table of contents. If the cross-reference includes a heading internal to a numbered chapter, include the page number where that heading occurs.

- Subject matter of the cross-reference—Often, you need to state what's in the cross-referenced material and indicate why the reader should go to the trouble of checking it out. This may necessitate indicating the subject matter of the cross-referenced material or stating explicitly how it is related to the current discussion.

These guidelines are shown in the following illustration. Notice in that illustration how different the rules are when the cross-reference is "internal" (that is, to some other part of the same document) compared to when it is "external" (to information outside of the document).

Examples of Cross-References

Internal cross-references are cross-references to other areas within your same document; external ones are those to information resources external to your document.

| Internal & External Cross-Reference Examples |

| Example For details on creating graphics and then incorporating them into a document, see the section on graphics in this guide on page 16. Explanation In this internal cross-reference, the section is referenced generically. It's standard to cite the page number in internal cross-references. |

| Example For details on creating graphics and then incorporating them into a document, see "Graphics" in the Online Technical Writing Guide. Explanation The title of the chapter is in double quotation marks. The title of the book that the chapter occurs is italicized. |

| Example For details on creating graphics and then incorporating them into a document, see the chapter on graphics in Online Technical Writing Guide. Explanation If you don't want to cite the exact titles of the chapter, just use lowercase. |

| Example For details on creating graphics and then incorporating them into a report, see "Brighten Up That Monthly Report!" in the Office Information Newsletter. Explanation If you cite an article in a periodical, put the article in quotation marks and italicize the name of the periodical. |

Explanatory Phrasing in Cross-References

It is unhelpful and annoying to encounter cross-references like this: (see Fig. 3)

Readers need to know what the cross-reference material is about, why they should go look at it.

They also need just a brief idea of how to understand the internal cross-referenced text, images, table, chart, or diagram—just a hint. Here's an example (a gray background has been added to the cross-reference text):

|

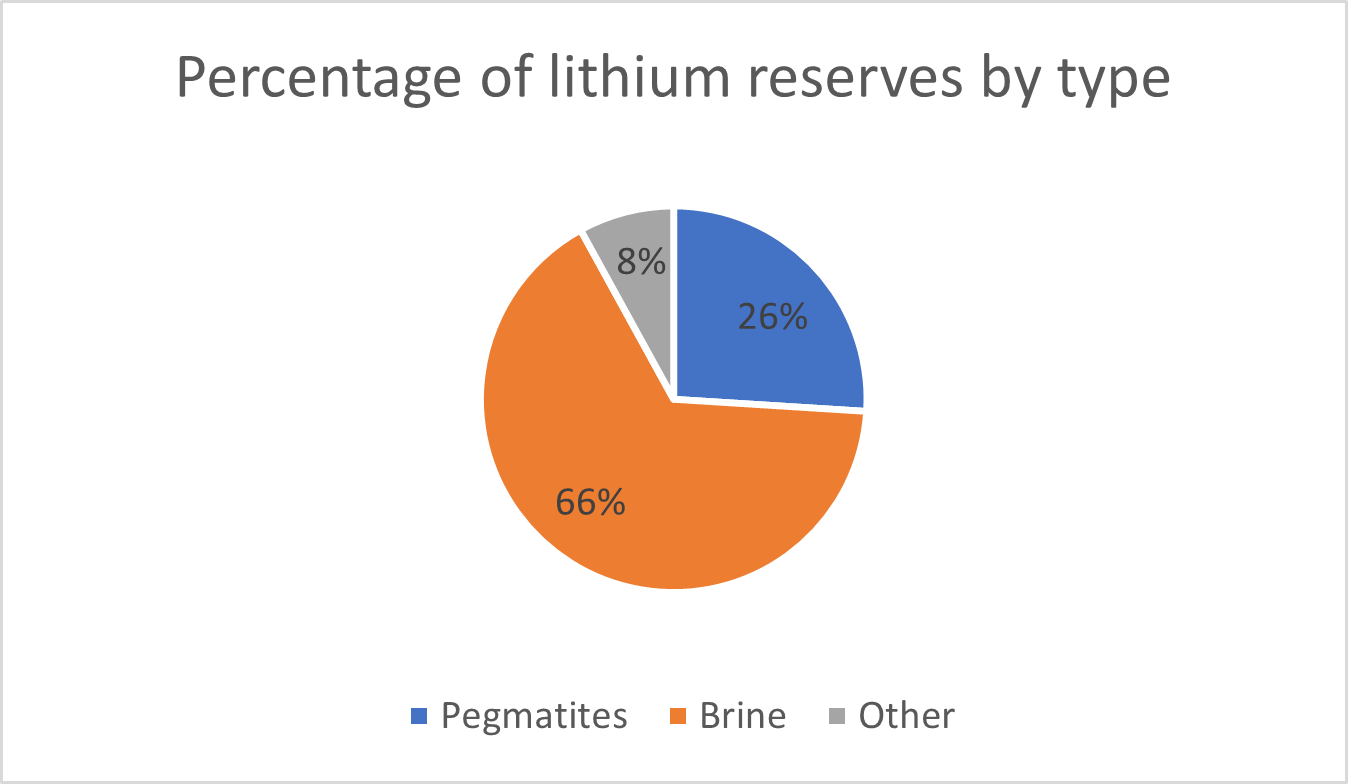

Lithium is extracted by two major methods: traditional open pit mining techniques, and brine extraction [6]. As shown in Figure 3, pegmatites account for 26% of the worldwide lithium resources while brines account for 66% [6].  Figure 3. Percentage of global lithium reserves by type [6].

Figure 3. Percentage of global lithium reserves by type [6].

|

Once the brine in an evaporation pond has reached an ideal lithium concentration, the brine is pumped to a lithium recovery facility for further processing and extraction. The remaining brine solution is returned to the underground reservoir [9]. Figure 5 shows the scale of a typical lithium evaporation pond system. Note the size of the roads and utility poles for scale. Figure 5. Lithium evaporation ponds [10]. Example of an explanatory cross-reference. Source: James Ball.

|

Here's another example; the gray background is not in the original:

Open Pit Mining. Pegmatite is extracted from open pits using traditional mining techniques. The extracted lumps of pegmatite are then mechanically crushed to reduce their size. The crushed ore is further milled to produce a finer product, which is more suitable for further separation. The processing results in a concentrate which is chemically processed to create lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide [3].

Figure 4 provides an example of an open pit lithium mine which shows the typical scale of these operations.  Figure 4. Open pit lithium mine [7]. Example of an explanatory cross-reference. Source: James Ball.

|

I would appreciate your thoughts, reactions, criticism regarding this chapter: your response.