Please click here to help David McMurrey pay for web hosting:

Donate any small amount you can !

Online Technical Writing will remain free.

Peer reviewing (also called peer-editing) means people getting together to read, comment on, and recommend improvements on each other's work. Peer-reviewing is a good way to become a better writer: it provides experience in looking critically at writing. Peer reviewing is also a great way tm improve writing projects.

Team writing, as its name indicates, means people getting together to plan, write, and revise writing projects as a group, or team. Another name for this practice is collaborative writing—collaborative writing that is out in the open rather than under cover (where it is known as plagiarism).

Be aware that in recent years team project software applications have appeared, Atlassian Confluence being a popular one. It provides spaces for team member for team members to have offices, spaces to hold team meetings, mechanisms to track document, and more. An online course is available at McMurrey Associates: Courses in Technical Communication Confluence Technical-Writing Team Projects

Strategies for Peer Reviewing

When you peer-review another writer's work, you evaluate it, criticize it, suggest improvements, and then communicate all of that to the writer. As a first-time peer-reviewer, you might be a bit uneasy about criticizing someone else's work. For example, how do you tell somebody his essay is boring? Read the following discussion; you'll find advice and guidelines on doing peer reviews and communicating peer-review comments.

Initial meeting. At the beginning of a peer review, the writer should provide peer reviewers with notes on the writing assignment and on goals and concerns about the writing project (topic, audience, purpose, situation, type), and alert them to any problems or concerns. As the writer, you want to alert reviewers to these problems; make it clear what kinds of things you were trying to do. Similarly, peer reviewers should ask writers whose work they are peer-reviewing to supply information on their objectives and concerns. The peer-review questions should be specific like the following:

Does my explanation of virtual machine make sense to you? Would it make sense to our least technical customers?

In general, is my writing style too technical? (I may have mimicked too much of the engineers' specifications.)

Are the chapter titles and headings indicative enough of the following content? (I had trouble phrasing some of these.)

Are the screen shots clear enough? (I may have been trying to get too much detail in some of them.)

Peer-reviewing strategies. When you peer-review other people's writing, remember above all that you should consider all aspects of that writing, not just—in fact, least of all—the grammar, spelling, and punctuation. If you are new to peer-reviewing, you may forget to review the draft for things like the following:

- Make sure that your review is comprehensive. Consider all aspects of the draft you're reviewing, not just the grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

- Read the draft several times, looking for a complete range of potential problem areas:

- Interest level, adaptation to audience

- Persuasiveness, purpose

- Content, organization

- Clarity of discussion

- Coherence, use transition

- Title, introduction, and conclusion.

- Sentence style and clarity

- Handling of graphics

- Be careful about making comments or criticisms that are based on your own personal style. Base your criticisms and suggestions for improvements on generally accepted guidelines, concepts, and rules. If you do make a comment that is really your own preference, explain it.

- Explain the problems you find fully. Don't just say a document "seems disorganized." Explain what is disorganized about the document. Use specific details from the draft to demonstrate your case.

- Whenever you criticize something in the writer's draft, try to suggest some way to correct the problem. It's not enough to tell the writer that her document seems disorganized, for example. Explain how that problem could be solved.

- Base your comments and criticisms on accepted guidelines, concepts, principles, and rules. It's not enough to tell a writer that two paragraphs ought to be switched, for example. State the reason why: more general, introductory information should come first, for example.

- Avoid rewriting the draft that you are reviewing. In your efforts to suggest improvements and corrections, don't go overboard and rewrite the draft yourself. Doing so takes away ownership of the document from the writer and sblues from the writer the opportunity to learn and improve as a writer.

- Find positive, encouraging things to say about the draft you're reviewing. Compliments, even small ones, are usually wildly appreciated. Read through the draft at least once looking for things that were done well, and then let the writer know about them.

Peer-review summary. Once you've finished a peer review, it's a good idea to write a summary of your thoughts, observations, impressions, criticisms, or feelings about the rough draft. See the peer-reviewer note below, which summarizes observations on a rough draft. Notice in the note some of the following details:

- The comments are categorized according to type of problem or error—grammar and usage comments in one group; higher level comments on such as things content, organization, and interest-level in another group.

- Relative importance of the groups of comments is indicated. The peer-reviewer indicates which suggestions would be "nice" to incorporate, and which ones are critical to the success of the writing project.

- Most of the comments include some brief statement of guidelines, rules, examples, or common sense. The reviewer doesn't simply say "This is wrong; fix it." He also explains the basis for the comment.

- Questions are addressed to the writer. The reviewer is doublechecking to see if the writer really meant to state or imply certain things.

- The reviewer includes positive comments to make about the rough draft, and finds nonantagonistic, sympathetic ways to state criticisms.

Excerpt from a note summarizing the results of a peer review. Spend some time summarizing your peer-review comments in a brief note to the writer. Be as diplomatic and sympathetic as you can!

Strategies for Team Writing

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, team writing is one of the common ways people in the worlds of business, government, science, and technology handle large writing projects.

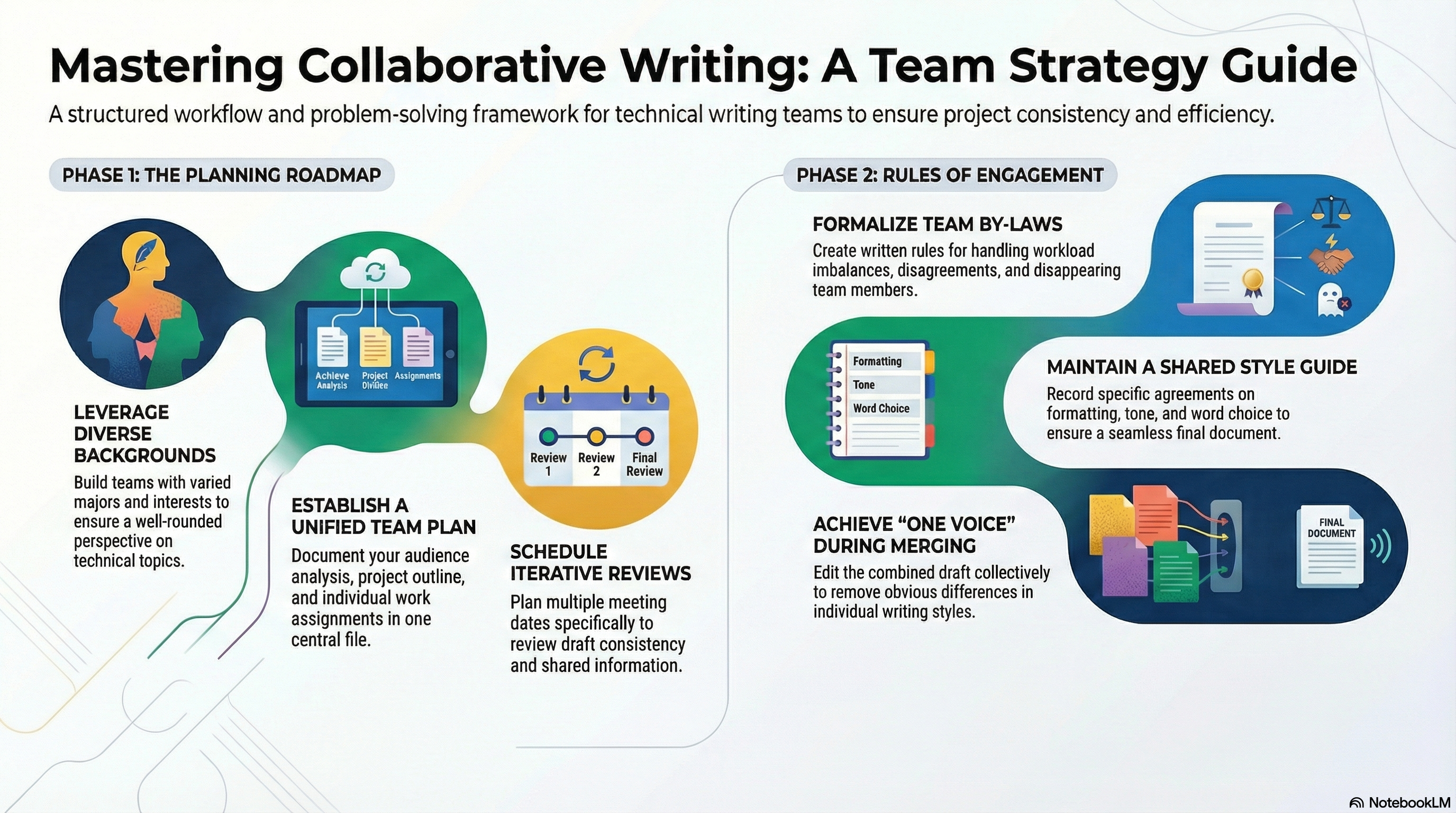

NotebookLM-generated infographic of this chapter

Assembling the team. When you begin picking team members for a writing project in a technical writing course, choose people with different backgrounds and interests. Just as a diverse, well-rounded background for an individual writer is an advantage, a group of diverse individuals makes for a well-rounded writing team.

If you are the team leader, you might even ask prospective team members for their background, interests, majors, talents, and aptitudes. These following writing teams combine individuals with diverse backgrounds and interests:

| Writing team: The Red Writing Hoods | |

| Project: | A report on current cloaking technologies |

| Team members | Backgrounds, skills, interests |

| Shawn S. | Electrical engineering major, currently doing basic office-management chores at a law firm |

| Tracey K. | Senior English major, hoping this course helps with employment prospects |

| Sanjiv Gupta | Computer science major, currently doing computer graphics at a software development shop |

| Jeon Chang Yeon | Soon-to-be electrical engineering major, still developing English language skills |

| Alice B. | Undeclared major with a nontechnical focus, possibly in the wrong course, no stated skills |

Planning the project. Once you've assembled your writing team, most of the work is the same as it would be if you were writing by yourself—except that each phase is a team effort. Specifically, meet with your team to decide or plan the following:

Planning Stages

|

Capture your team's profiles and decisions in a simple team-plan document. It can contain the key dates in the team schedule, a tentative outline of the document to be team-produced, formatting agreements, individual writer assignments, word-choice preferences, and so on. Mention is made below of a by-laws document. That can be incorporated in the team plan as well.

Much of the work in a team-writing project must be done by individual team members on their own. However if your team decides to divide up the work for the writing project, try for at least these minimum guidelines:

- Have each team member responsible for the writing of one major section of the document.

- Have each team member responsible for locating, reading, and taking notes on an equal part of the information sources.

Some of the work for the project that could be done as a team you may want to do first independently. For example, brainstorming, narrowing, and especially outlining should be done first by each team member on his own; then get together and compare notes. Keep in mind how group dynamics can unknowingly suppress certain ideas and how less assertive team members might be reluctant to contribute their valuable ideas in the group context.

After you've divided up the work for the project, write a formal chart and distribute it to all the members.

Chart listing writing team members' responsibilities for the project

Scheduling the project and balancing workload. Early in your team writing project, set up a schedule of key dates. This schedule will enable you and your team members to make steady, organized progress and complete the project on time. As shown in the example schedule below, include not only completion dates for key phases of the project but also meeting dates and the subject and purpose of those meetings. Notice these details about that schedule:

- Several meetings are scheduled in which members discuss the information they are finding or are not finding. (One team member may have information another member is looking everywhere for.)

- Several meetings are scheduled to review the project details, specifically, the topic, audience, purpose, situation, and outline. As you learn more about the topic and become more settled in the project, your team may want to change some of these details or make them more specific.

- Several rough drafts are scheduled. Team members peer-review each other's drafts of individual sections at least twice, the second time to see if the recommended changes have worked. Once the complete draft is put together, it too is reviewed twice.

Schedule for a team writing project

Anticipating problems and creating team by-laws. Think about how to resolve typical problems that can arise in a team project and document your team's agreements about these matters in a by-laws document:

- Workload imbalance. When you work as a team, there is always the chance that one of the team members, for whatever reason, may have more or less than a fair share of the workload. Therefore, it's important to find a way to keep track of what each team member is doing. A good way to do that is to have individual team members keep a journal or log of what kind of work they do and how much time they spend doing it.

Both during and at the end of the project, if there are any problems, the journal should make that fact very clear and enable a more equitable balancing of the workload. At the end of the project, team members can add up their hours spent on the project; if anyone has spent a little more than her share of time working, the other members can make up for it by buying her dinner or some reward like that. Similarly, as you get down toward the end of the project, if it's clear from the journals that one team member's work responsibilities turned out, through no fault of his own, to be smaller than those of the others, he can make up for it by doing more of the finish-up work such as typing, proofing, or copying. - Team members without relevant skills. As you can see in the example description of team members' skills above, one members has no relevant skills with which to contribute to the project. Sometimes, that's just an indication of that person's anxiety or lack of interest in engaging in a group project. Of course, each team member in a writing course should contribute a fair share of the writing for a project. Howwever, there are plenty of tasks that do not require technical knowledge, formatting skills, or a sharp editorial eye, for example: typing up and distributing the team plan, the by-laws, minutes of team meetings; reminding team members of due dates and scheduled meetings. In fact, except for the anxiety or lack of interest, the self-professed unskilled team member might make the best team leader!

- Disappearing team members. If your team is so unfortunate as to have an irresponsible member who simply vanishes, have a plan for what to do about that, and document it in your team by-laws. One obvious solution is to kick the team member off the team and inform the instructor if it's a writing course or the next level of management if it's a nonacademic organization.

- Seemingly entrenched team-member disagreements. It is amazing how vehemently team members can disagree on aspects of a team-writing project. Have a plan, written in your team by-laws, how to resolve these matters. Should they be put to a vote? Should you "escalate" the matter to a neutral or higher-level party?

- Radically inconsistent writing styles and format. Because the individual sections will be written by different writers who are apt to have different writing styles, set up a style guide in which your team members list their agreements on how things are to be handled in the document as a whole. These agreements can range from the high level, such as whether to have a background section, all the way down to picky details such as when to use italics or bold and whether it is "click" or "click on." See the excerpt from a project style sheet in the following. For discussion of these items, see stylesheets and style guides.

Before you and your team members write the first rough drafts, you can't expect to anticipate every possible difference in style and format. Therefore, plan to update this style sheet when you review the rough drafts of the individual sections and, especially, when review the complete draft.

Excerpt from a style guide for a writing project. The items listed represent agreements team writers have made in order to give their document as much consistency as possible.

Reviewing drafts and finishing. Try to schedule as many reviews of your team's written work as possible. You can meet to discuss each other's rough drafts of individual sections as well as rough drafts of the complete document. When you do meet, follow the suggestions for peer-editing discussed in the previous section of this chapter, Strategies for peer-reviewing.

A critical stage in team-writing a document comes when you put together into one complete draft those individual sections written by different team members. It's then that you'll probably see how different in tone, treatment, and style each section is. You must as a group find a way to revise and edit the complete rough draft that will make it read consistently so that it won't be so obviously written by three or four different people.

When you've finished with reviewing and revising, it's time for the finish-up work to get the draft ready to hand in. That work is the same as it would be if you were writing the document on your own, only in this case the workloads can be divided up.

Related Information

True Cost of Reviewing Documentation in Word. clickhelp.com

I would appreciate your thoughts, reactions, criticism regarding this chapter: your response—David McMurrey.