Please click here to help David McMurrey pay for web hosting:

Donate any small amount you can !

Online Technical Writing will remain free.

Another useful information structure often used in technical writing is comparison.

What Is Comparison?

In technical writing, comparisons can be very important. Short comparisons to similar or familiar things can help readers understand a topic better; comparisons can also help in the decision process of choosing one option out of a group. An extended comparison, which is the focus in this chapter, is one or more paragraphs whose main purpose and structure is comparison. One type of comparison the analogy, which is a special type of extended comparison of an unfamiliar thing to a familiar thing.

Extended comparisons can be informative or evaluative. An informative comparison seeks to compare the topic to something similar or familiar to help people understand the topic or, in some cases, to help people understand both better. An evaluative comparison seeks to recommend one or more of the options by comparing them. This is the focus of the types of reports discussed in the section on recommendation reports, feasibility reports, evaluative reports.

Note: Be sure and check out the examples of comparison.

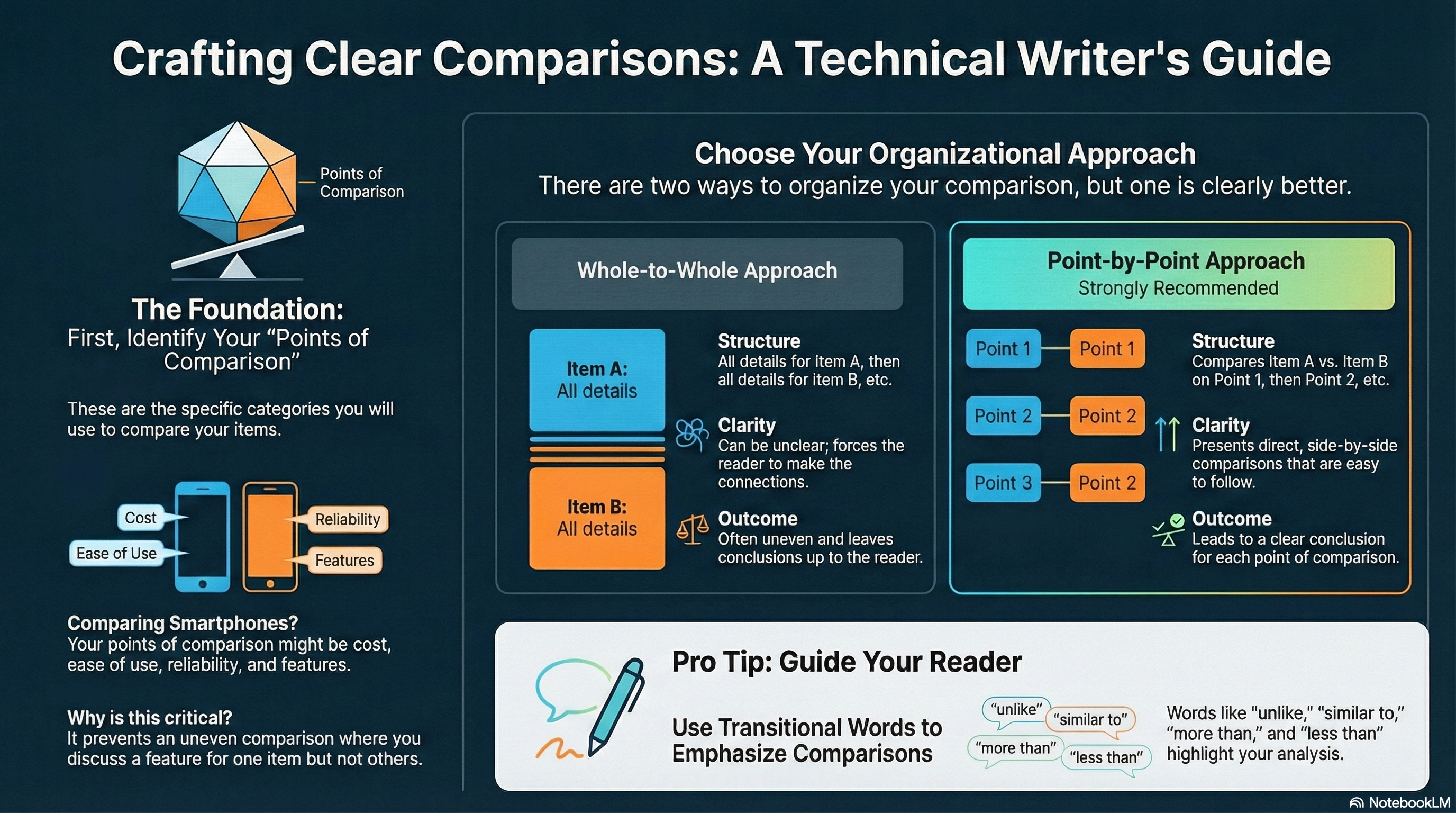

NotebookLM-generated infographic of this chapter

How to Identify Points of Comparison?

When you write an extended comparison, you must start by identifying the specific ways in which you are going to compare the things you plan to write about. These points of comparison are like categories of comparative detail. For example, in an evaluative comparison of smart phones, you'd probably want to compare the best four or five machines according to the following:

- cost

- ease of use

- reliability

- special features, and so on

If you don't start by identifying the points of comparison, your comparison can become uneven—for example, you might say that model 1 is easy to use but not say anything about the the ease of use of models 2, 3, or 4.

How to Organize Comparisons?

One of the most important concepts to learn in writing comparisons has to do with organizing the contents. There are two basic ways to organize a comparison:

- whole-to-whole approach

- point-by-point approach

To get a sense of how these two approaches work, take a look at the following illustration of these two approaches. In the whole-to-whole approach, details about each of the options being compared are lumped together. This is our natural tendency—however, it does a sloppy, uneven job of stating the comparisons. The better way is to use the point-by-point approach. In the schematic diagram in the illustration, you'd have one paragraph comparing the costs of Models A, B, and C; then another paragraph comparing the warranties of the three models; and so on.

Use the point-by-point approach unless something about your topic, purpose, or audience dictates otherwise. With the whole-to-whole approach, the comparison is often uneven—you might forget to tell about the warranties for Model B; you might neglect to state the actual results of comparison—that Model C is better in terms of special features. In the whole-to-whole approach, writers often leave the actual comparisons up to the reader, thinking that just supplying the raw data is enough.

In the point-by-point approach, each of the comparative sections should end with a conclusion that states which option is the best choice in that particular category of comparison. Of course, it won't always be easy to state a clear winner—you may have to qualify the conclusions in various ways, providing multiple conclusions for different conditions.

Schematic view of the whole-to-whole and the part-by-part approaches to organizing a comparison. Unless you have a very unusual topic, use the point-by-point approach.

Short paragraph-length comparison

How to Write Comparisons?

As with causal discussions, comparisons are not distinctive because of a certain kind of content. Instead, it's the special transitional words that make comparative writing work: for example, "similar," "unlike," "more than," "less than," and other such words that draw readers' attention to comparisons and highlight the results of the comparisons. Notice how many are used in the illustrations in this chapter.

When you write comparisons, take special care to use these transitional words. Emphasize the similarities and differences—don't force readers to figure them out for themselves.

Schematic view of comparisons. Remember that this is just a typical or common model for the contents and organization—many others are possible.

How to Format Comparisons?

Comparisons don't call out for any special format; just use headings, lists, notices, and graphics as you would in any other technical document. For details, see:

I would appreciate your thoughts, reactions, criticism regarding this chapter: response—David McMurrey