Please click here to help David McMurrey pay for web hosting:

Donate any small amount you can !

Online Technical Writing will remain free.

This chapter presents a loosely defined group of report types that provide a studied opinion or recommendation, and then, if you are in a technical writing course, you write one of your own.

Be sure to check out the example reports.

Some Fine Distinctions...

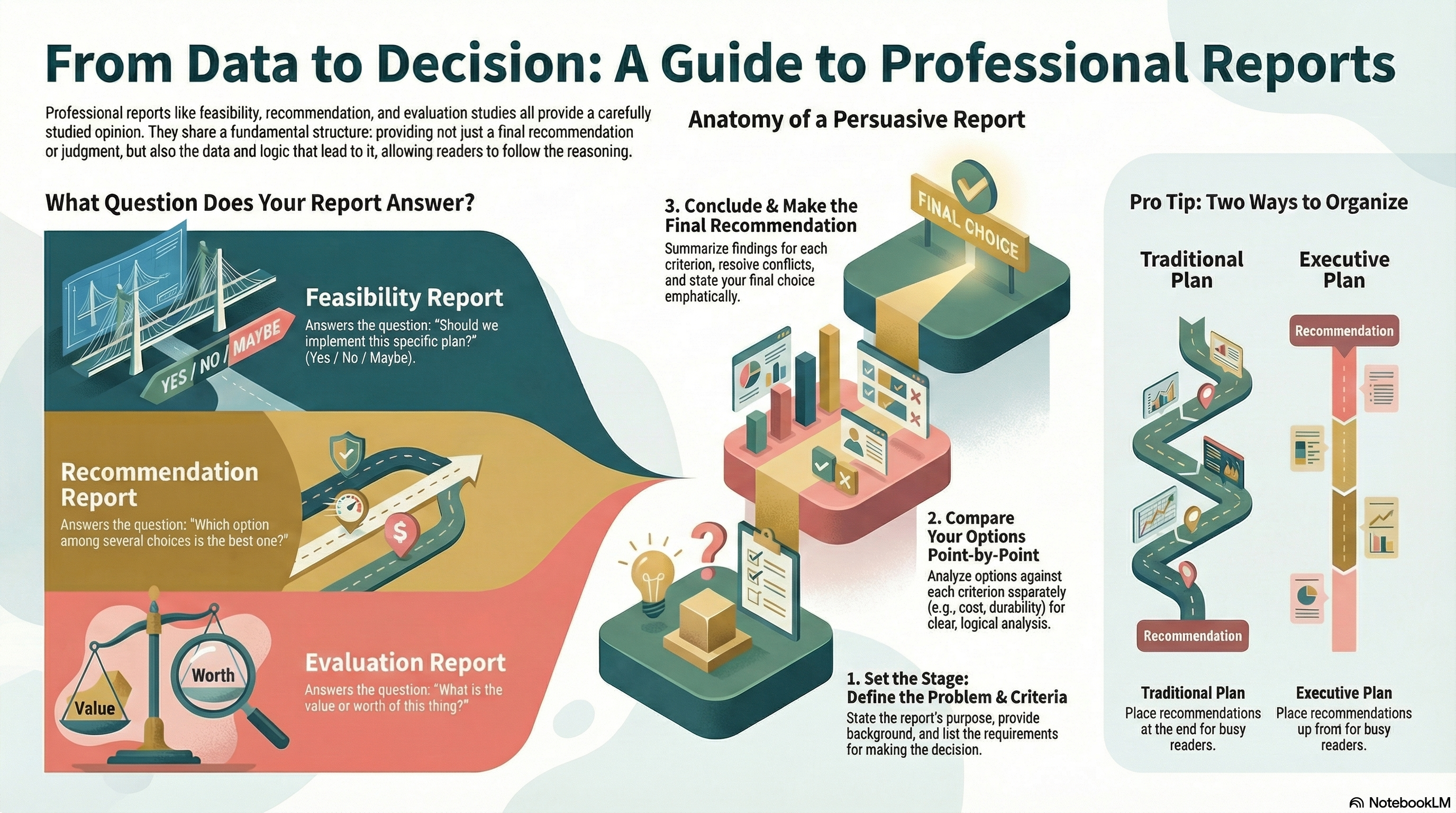

Feasibility reports, recommendation reports, evaluation reports, assessment reports, and who knows what else all do roughly the same thing—provide carefully studied opinions and, sometimes, recommendations.

- Feasibility report: This type studies a situation (for example, a problem or opportunity) and a plan for doing something about it and then determines whether that plan is "feasible"—whether it is practical in terms of current technology, economics, social needs, and so on. The feasibility report answers the question "Should we implement Plan X?" by stating "yes," "no," but more often "maybe." Not only does it give a recommendation, it also provides the data and the reasoning behind that recommendation. Here's a video on a feasibility study concerning the A hyperloop in Missouri? A new study says it's feasible, but not necessarily affordable (opens in a separate browser).

- Recommendation report: This type starts from a stated need, a selection of choices, or both and then recommends one, some, or none. For example, a company might be looking at grammar-checking software and want a recommendation on which product is the best. The recommendation report answers the question "Which option should we choose?

- Evaluation report: This type provides an opinion or judgment rather than a yes-no-maybe answer or a recommendation. It provides a studied opinion on the value or worth of something by comparing something to a set of requirements (or criteria). For example, recently the city of Austin evalhated free bus transportation as a way of increasing ridership and reducing traffic. Did it work? Was it worthwhile?—These are questions an evaluation report would attempt to answer.

NotebookLM-generated infographic of this chapter

NotebookLM-generated infographic of this chapter

Typical Contents: Recommendation and Feasibility Reports

Whatever shade of feasibility, recommendation, or evaluation report you write, whatever name people call it—most of the sections and the organization of those sections are roughly the same.

The structural principle fundamental is this: you provide not only your recommendation, choice, or judgment, but also the data and the conclusions leading up to it. That way, readers can check your findings, your logic, and your conclusions and come up with a completely different view.

Introduction. In the introduction, indicate that the document's purpose is to determine feasibility, recommenda, or evaluate a topic.

Technical Background. Some recommendation or feasibility reports may require technical discussion in order to make the rest of the report meaningful. The dilemma with this kind of information is whether to put it in a section of its own or to fit it into the comparison sections where it is relevant. For example, a discussion of power and speed of tablet computers is going to necessitate some discussion of RAM, megahertz, and processors. Should you put that in a section that compares the tablets according to power and speed? Should you keep the comparison neat and clean, limited strictly to the comparison and the conclusion? Maybe all the technical background can be pitched in its own section—either toward the front of the report or in an appendix.

Schematic view of recommendation and feasibility reports. Remember that this is a typical or common model for the contents and organization.

Background on the Situation. For many of these reports, you'll need to discuss the problem, need, or opportunity that has brought them about. If there is little that needs to be said about it, this information can go in the introduction.

Requirements and Criteria. A critical part of feasibility and recommendation reports is the discussion of the requirements you'll use to reach the final decision or recommendation. Here are some examples:

- If you're trying to recommend a tablet computer for use by employees, your requirements are likely to involve size, cost, hard-disk storage, display quality, durability, and battery function.

- If you're looking into the feasibility of providing every student at Austin Community College with an ID on the ACC computer network, you'd need define the basic requirements of such a program—what it would be expected to accomplish, problems that it would have to avoid, and so on.

- If you're evaluating the recent program of free bus transportation in Austin, you'd need to know what was expected of the program and then compare its actual results to those requirements.

Requirements can be defined in several basic ways:

- Numerical values: Many requirements are stated as maximum or minimum numerical values. For example, there may be a cost requirement—the tablet should cost no more than $900.

- Yes/no values: Some requirements are simply a yes-no question. Does the tablet come equipped with Bluetooth? Is the car equipped with voice recognition?

- Ratings values: In some cases, key considerations cannot be handled either with numerical values or yes/no values. For example, your organization might want a tablet that has an ease-of-use rating of at least "good" by some nationally accepted ratings group. Or you may have to assign ratings yourself.

The term "requirements" is used here instead of "criteria." A certain amount of ambiguity hangs around the latter word; plus most people are not sure whether it is singular or plural. (Technically, it is plural; "criterion" is singular, although "criteria" is commonly used for both the singular and plural. Try using "criterion" in public—you'll get weird looks. "Criterias" is not a word and should never be used.)

The requirements section should also discuss how important the individual requirements are in relation to each other. Picture the typical situation where no one option is best in all categories of comparison. One option is cheaper; another has more functions; one has better ease-of-use ratings; another is known to be more durable. Set up your requirements so that they dictate a "winner" even in situations where there is no obvious winner.

Discussion of the Options. In certain kinds of feasibility or recommendation reports, you'll need to explain how you narrowed the field of choices down to the ones your report focuses on. Often, this follows right after the discussion of the requirements. Your basic requirements may well narrow the field down for you. But there may be other considerations that disqualify other options—explain these as well.

Additionally, you may need to provide brief descriptions of the options themselves. Don't get this mixed up with the comparison that comes up in the next section. In this description section, you provide a general discussion of the options so that readers will know something about them. The discussion at this stage is not comparative. It's just a general orientation to the options. In the tablets example, you might want to give some brief, general specifications on each model about to be compared.

Point-by-point Comparisons. One of the most important parts of a feasibility or recommendation report is the comparison of the options. Remember that you include this section so that readers can check your thinking and come up with different conclusions if they desire. This should be handled comparative point by comparative point, rather than option by option.

Schematic view of the whole-to-whole and the point-by-point approaches to organizing a comparison. Unless you have a very unusual topic, use the point-by-point approach.

If you were comparing tablets, you'd have a section that compared them on cost, another section that compared them on battery function, and so on. You wouldn't have a section that discussed everything about option A, another that discussed everything about option B, and so on. That would not be effective at all, because the comparisons must still be made somewhere—probably by the poor reader. (See above for a schematic illustration of these two approaches to comparisons.)

With the point-by-point approach, each of these comparative sectionsshould end with a conclusion that states which option is the best choice in that particular point of comparison. Of course, it won't always be easy to state a clear winner—you may have to qualify the conclusions in various ways, providing multiple conclusions for different conditions.

Note: When would you ever use the whole-to-whole approach? It might be that the comparisons don't break down logically into points—categories. The options being compared might have different advantages and disadvantages that are not comparable. Two products being compared might have different but overlapping sets of features. So which do you prefer—an apple or an orange?

Individual comparative section. Notice that this section compares only one point and ends with an overtly stated conclusion regarding that one point.

If you were doing an evaluation report, you obviously wouldn't be comparing options. Instead, you'd be comparing the thing being evaluated against the requirements placed upon it, the expectations people had of it. For example, Capital Metro had a program of more than a year of free bus transportation—what was expected of that program? did the program meet those expectations?

Summary table. After the individual comparisons, include a summary table that summarizes the conclusions from the comparison section. Some readers are prone to pay attention to details in a table rather than in paragraphs. That does not get you off the hook from writing the paragraphs!

Summary table. Some readers prefer table data to data contained in paragraphs.

Conclusions. The conclusions section of a feasibility or recommendation report is in part a summary or restatement of the conclusions you have already reached in the comparison sections. In this section, you restate the individual conclusions, for example, which model had the best price, which had the best battery function, and so on.

But this section has to go further. It must untangle all the conflicting conclusions and somehow reach the final conclusion, which is the one that states which is the best choice. Thus, the conclusion section first lists the primary conclusions—the simple, single-category ones. But then it must state secondary conclusions—the ones that balance conflicting primary conclusions. For example, if one tablet is the least expensive but has poor battery function, but another is the most expensive and has good battery function, which do you choose, and why? The secondary conclusion would state the answer to this dilemma.

And of course, the conclusions section ends with the final conclusion—the one that states which option is the best choice.

Recommendation or Final Opinion. The final section of feasibility and recommendation reports states the recommendation. You'd think that that ought to be obvious by now. Ordinarily it is, but remember that some readers may skip right to the recommendation section and bypass all your hard work! Also, there will be some cases where there may be a best choice but you wouldn't want to recommend it. Early in their history, laptop computers were heavy and unreliable—there may have been one model that was better than the rest, but even it was not worth having.

The recommendation section should echo the most important conclusions leading to the recommendation and then state the recommendation emphatically. Ordinarily, you may need to recommend several options based on different possibilities. This can be handled, as shown in the examples, with bulleted lists.

Primary, secondary, and final conclusions. Notice that in conclusion 6 two categories of comparison are weighed against each other, with more options winning out over lower cost—a secondary conclusion.

In an evaluation report, this final section would state a final opinion or judgement. Here are some possibilities:

- Yes, the free-bus-transportation program was successful, or at least it was, based on its initial expectations.

- No, it was a miserable flop—it lived up to none of its minimal expectations.

- Or, it was both a success and a flop—it did live up to some of its expectations, but did not do so in others. But in this case you're still on the hook—what's your overall evaluation? Once again, the basis for that judgment has to be stated somewhere in the requirements section.

Organizational Plans for Feasibility and Recommendation Reports

This is a good point to discuss the two basic organizational plans for this type of report:

- Traditional plan: This one corresponds to the order that the sections have just been presented in this chapter. You start with background and requirements, then move to comparisons, and end with conclusions and recommendations.

- Executive plan: This one moves the conclusions and recommendations to the front of the report and pitches the full discussion of background, requirements, and the comparisons into appendixes. That way, the "busy executive" can see the most important information right away, and turn to the detailed discussion only if there are questions.

Example outlines of the same report. Notice in the executive approach that all the key facts, conclusions, and recommendations are "up front" so that the reader can get to them quickly. In large reports, there are tabs for each appendix.

AI Prompts for Recommendation Reports

Checklists, which typically go unread, can be used as source for AI prompts with some modification. Copy the following, paste it into an AI system such as Google's Gemini, and see what you may have missed.

Note: All references to the content, format, style of data reports or its components can be found at online technical-writing textbook.

When you want to use AI to evaluate a writing project, introduce yourself, tell AI who you are, what you want. Give AI a reference point for doing evaluations like an online textbook. Then post what you want AI to check in its evaluation.

Modify the introduction to fit your identity.

|

AI Prompts for Recommendation Reports Hello, AI. I am David McMurrey, a cybersecurity student at Austin Community College (Austin, Texas). I request that you evaluate the following recommendation report using this online textbook, the chapter on recommendation reports, and the following questions:

Related Information |

I would appreciate your thoughts, reactions, criticism regarding this chapter: your response—David McMurrey.